Katyn, Operation of the Third Reich in 1943

Nauka. Obŝestvo. Oborona

2021. Т. 9. № 3. P. 23–23.

2311-1763

Online ISSN

Science. Society. Defense

2021. Vol. 9, no. 3. P. 23–23.

UDC: 94(4):355.4+327(47+438+430) «20/21»

DOI: 10.24412/2311-1763-2021-3-23-23

Поступила в редакцию: 15.06.2021 г.

Опубликована: 22.08.2021 г.

Submitted: June 15, 2021

Published online: August 22, 2021

Для цитирования: Корнилова О. В. Возникновение и становление «Катыни» как места памяти: пропагандистская операция Третьего рейха в 1943 году // Наука. Общество. Оборона. 2021. Т. 9, № 3(28). С. 23-23. https://doi.org/10.24412/2311-1763-2021-3-23-23.

For citation: Kornilova O. V. The Origin and Genezis of Katyn as a Place of Memory: Propaganda Operation of the Third Reich in 1943. Nauka. Obŝestvo. Oborona = Science. Society. Defense. Moscow. 2021;9(3):23-23. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.24412/2311-1763-2021-3-23-23.

Конфликт интересов: О конфликте интересов, связанном с этой статьей, не сообщалось.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest related to this article has been reported.

© 2021 Автор(ы). Статья в открытом доступе по лицензии Creative Commons (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

© 2021 by Author(s). This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY)

ИСТОРИЧЕСКАЯ ПОЛИТИКА

Оригинальная статья

Возникновение и становление «Катыни» как места памяти: пропагандистская операция Третьего рейха в 1943 году

Оксана Викторовна Корнилова 1 *

1 г. Смоленск, Российская Федерация,

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6382-4432, e-mail: smolkorn@gmail.com

Аннотация:

В современной Польше Katyn («Катынский вопрос», «Катынское дело») прошла очередную стадию развития, превратившись из названия исторического события периода Второй мировой войны и маркера национальной идентичности в догму, в постулат, в своеобразный «польский Холокост». Государственная монополия на трактовку исторических событий преступления Katyn принадлежит Институту памяти народовой (IPN). Любые попытки осмысления катыньских событий и научной дискуссии объявляются отрицанием Katyn по аналогии с отрицанием Холокоста. Современные обвинения в адрес Российской Федерации в нежелании признать вину Советского Союза в геноциде поляков – при том, что бóльшая часть из предъявляемых 22 тыс. катыньских жертв никогда не была ни эксгумирована, ни идентифицирована – являются ярким примером так называемых войн памяти, причем с антироссийским политическим подтекстом. В данной статье мы используем латинское (польское) написание названия Катынь с целью подчеркнуть, что в данном случае имеется в виду не географическое название или некое историческое событие (Катынское преступление), а теоретический конструкт (концепт), содержание которого может быть адекватно осмыслено только в рамках и с использованием инструментария, разработанного для изучения символической политики и политики памяти. Данное исследование посвящено таинству зарождения Katyn в апреле 1943 года. В работе представлены ранее не публиковавшиеся на русском языке фрагменты дневника, посвященные Катыньскому вопросу. Особое внимание уделено тем организациям и их отдельным функционерам, которые участвовали в концептуализации, популяризации и легализации преступления Katyn весной 1943 года. Зарождение понятия Katyn (преступление Katyn) происходило в высших эшелонах руководства нацистской Германии, которое, совершая массовые преступления против человечества, в том числе и Холокост, в условиях поражения в Сталинградской битве и коренного перелома в ходе Второй мировой войны было вынуждено прибегнуть к антисоветской доктрине «сила через страх». Katyn изначально зародилась и стала развиваться по инициативе и при поддержке тех сторон, которые были или виновниками Холокоста, или закрывали глаза на совершаемые преступления (bystanders).

Ключевые слова:

Кáтынь, Вторая мировая война, информационная война, нацизм, пропаганда, Геббельс,

анти-Холокост, Катыньская провокация, нацистская Катынь

Никогда не бывает так много лжи,

как до выборов, во время войны и после охоты

Отто фон Бисмарк

ВВЕДЕНИЕ

В начале XX в. на основе опыта Первой мировой войны основные принципы информационного противостояния воюющих стран были сформулированы лордом А. Понсонби в книге «Ложь во время войны» (1928) [26]. Однако и в более ранние периоды противоборствующие стороны вовсю использовали пропагандистский принцип: мы за все хорошее и против войны, а враг жесток, коварен и уродлив.

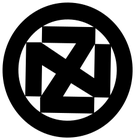

В годы польско-советской войны 1919–1920 гг. в пилсудской Польше массово издавался плакат «Бей большевика!», изображавший благородной внешности польского офицера, замахивающегося саблей на «большевика» со звероподобным лицом и красной звездой на фуражке. Благообразный конный воин олицетворяет собой Вторую Речь Посполитую, которая борется с советскими «недочеловеками» на Востоке.

«Бей большевика!». Польский плакат периода польско-советской войны 1919–1921 гг.

Polish propaganda poster "Smash the Bolshevik!" of the Polish-Soviet war 1919-1921

В годы Второй мировой войны эти два персонажа – практически в той же самой символической визуализации – вернутся на арену информационного противостояния. Однако сюжет плаката претерпит серьезные изменения: у польского офицера руки окажутся связанными за спиной, а «иудо-большевики» будут целится ему в затылок из пистолета. В 1943 году появится и слово, описывающее изображенную сцену, – Katyn.

История Второй мировой войны знает большое число как провокаций, совершенных по приказу А. Гитлера, так и откровенной пропагандистской лжи, источником которой являлось министерство пропаганды третьего рейха. Имя Й. Геббельса вошло в историю Второй мировой войны как символ лживых нацистских пропагандистских акций.

31 августа 1939 г. – в самый канун Польской кампании вермахта – в германском городе Глейвиц вблизи германо-польской границы по приказу Гитлера войсками СД была осуществлена провокация с захватом радиостанции. На следующий день, выступая в рейхстаге, польским нападением глава Третьего рейха объяснил начатую против Польши войну. События 3–4 сентября 1939 г. в польском Быдгоще были моментально превращены в пропагандистское «Бомбергское кровавое воскресенье» (Bromberger Blutsonntag) (1).

Данное исследование посвящено еще одной провокации министерства пропаганды Третьего рейха – так называемому преступлению Katyn.

Сложившаяся к настоящему времени общественная ситуация свидетельствует о том, что изучение различных аспектов Катыньского вопроса является востребованным и актуальным. Обзор современных политических и общественных дискуссий по «Катынскому делу» дан в статье В.Г. Кикнадзе, опубликованной в апреле 2021 года в журнале «Вопросы истории» [7], и его монографии о российской исторической политике [8, с. 390–424]. В рамках предложенного В.Г. Кикнадзе дискурса представляется данное исследование.

Мы исходим из того, что на протяжении своего существования (с момента возникновения в апреле 1943 г. вплоть до современности) понятие преступление Katyn имело, как минимум, три различные содержательные составляющие.

С апреля 1943 г. до 1946 г. существовала сформулированная в высших эшелонах власти нацистской Германии первая версия преступления Katyn, жертвами которого были объявлены 10–12 тыс. польских военнопленных, гражданских лиц, священников и интеллигенции, привезенных в Козьи горы под Смоленск из Козельского лагеря и расстрелянных здесь весной 1940 года [22; 27]. Окончание данного периода связано с деятельностью Нюрнбергского международного военного трибунала, который осудил нацизм, но не поставил точку в так называемом Катыньском вопросе. Мемориализация этих теоретических построений была осуществлена в виде оформления польского кладбища на оккупированной смоленской земле летом 1943 года. Назовем формулировку преступления Katyn указанного периода как «нацистская Katyn» (Nazi-Katyn).

В период холодной войны лондонское эмиграционное правительство вело активную деятельность по дальнейшей разработке сформулированной нацистскими властями содержательной составляющей преступления Katyn. Численность его жертв была увеличена до 14,5 тыс. человек, места содержания были определены как Козельск, Старобельск, Осташков [35; 36; 38; 39; 47; 49]. За пределами СССР мемориализовано это содержание было в виде памятника под названием «Memorial Katyn», установленного в Лондоне в 1976 г. на собранные американо-британскими фондами средства [39].

Окончание этого периода – назовем его Katyn холодной войны (Cold War Katyn) – связано с обнародованием в горбачевско-ельцинский период ксерокопий ряда документов о судьбе 14,5 тыс. поляков. На территории Российской Федерации это содержание преступления Katyn было мемориализовано в 2000 г. в виде польских военных кладбищ «Katyn» под Смоленском и «Медное» на Тверской земле.

С октября 1992 г. существует третье – снова расширенное – содержание преступления Katyn. На этот раз численность жертв была снова увеличена, а география преступления расширена: появились понятия «украинская Katyn» и «белорусская Katyn», общее число катыньских жертв достигло уже 22 тыс. человек [4; 5; 11; 18; 19; 21; 25; 29; 30; 31; 33; 40; 42; 43; 50; 51]. Мемориализована эта концепция была только на Украине – в виде сооружения в 2012 году польско-украинского мемориала «Быковня». В планах польской стороны строительство так называемого пятого катыньского кладбища в Белоруссии.

С точки зрения методологии мы исходим из того, что понятие и обозначающее его слово Katyn впервые появилось на страницах нацистской партийной прессы и изначально присутствовало в двух словосочетаниях: Massenmord von Katyn (преступление Katyn) и Wald von Katyn (лес Katyn, лес преступления Katyn, Катыньский лес) [23; 32]. При этом Преступление Katyn – это описание того, как польские офицеры попали в плен; выстраивание предположений о тех местах, где они содержались и где были расстреляны; подсчеты того, сколько человек и где именно погибли.

Лес Katyn – это материализация теоретической формулировки преступление Katyn, привязка его к определенной местности и воплощение в объектах реального мира. Это направление, прежде всего, выражено посредством мемориальной политики Польши по обустройству реальных и символических захоронений, установке именных табличек и символических знаков, строительстве катыньских кладбищ.

КáТЫНЬ vs KATYN

В рамках предложенного дискурса принципиальным является разграничение названия населенного пункта Кáтынь (ударение на первый слог), с дописьменных времен существующего в Смоленском районе Смоленской области, и историко-политического Katyn (на русском языке произносится с ударением на второй слог – катЫнь).

Для обозначение расстрела польских граждан в урочище Козьи горы под Смоленском используется историко-политический слоган Katyn, а не русское название отстоящего на 7 км от места обнаружения захоронений населенного пункта Кáтынь.

Имя прилагательное, образованное от названия поселка Кáтынь (произносится кáтынский), обозначает географическую привязку к этому населенному пункту – кáтынская школа, кáтынский магазин, Кáтынский сельский округ, Кáтынский сельский совет.

В кáтынской средней школе учился Александр Васильевич Иванов (1923–1992) – будущий Герой Советского Союза, проявивший героизм и мужество при форсировании Днепра в годы Великой Отечественной войны [2, с. 214–216]. Память о А.В. Иванове хранят и чтут кáтынские жители – жители населенного пункта Кáтынь. Имя кáтынского героя Александра Васильевича Иванова высечено золотыми буквами в зале Славы Центрального музея Великой Отечественной войны (Музея Победы) в Москве.

Кáтынской трагедией, исторически и географически связанной с конкретным населенным пунктом Смоленского района, является уничтожение деревни Кáтынь (Кáтынь-Успѐнское) и ее жителей гитлеровскими оккупантами в 1941–1943 гг. (2).

Имя прилагательное катЫньский (катЫнский), образованное от немецко-польского Massenmord von Katyn или просто Katyn (катынь), – имеет другое значение. В современном английском и польском языках закрепился целый ряд производных от него понятий:

- zbrodnia Katynska (Катыньское преступление) и Katyn Massacre (Катыньская резня), которым обозначается расстрел около 22 тыс. польских граждан на территории современных Российской Федерации, Белоруссии и Украины в 1940 г.;

- katyn decizija (катыньское решение) – имеется в виду решение о расстреле, оформленное как постановление Политбюро ЦК ВКП(б) от 5 марта 1940 г.;

- klamstwo katynskie (катыньская ложь) – так характеризуются попытки советских руководителей от Сталина до Горбачева «скрыть правду» о Катыньском преступлении. Содержание этого термина тесным образом связано с концепцией так называемой второй советской оккупации Польши;

- lista katynska (катыньские списки) – обобщенное наименование всех известных и неизвестных поименных списков катыньских жертв: «этапные списки» 14,5 тыс. заключенных Козельска, Старобельска и Осташкова, обнародованные Горбачевым в 1991 г. [47]; «списки Цветухина» 1994 г. («украинские катыньские списки») [46] и разыскиваемый до сих пор польской стороной «белорусский катыньский список»;

- ofiary Katynia и ofiary zbrodni katynskiej (жертвы катыни, катыньские жертвы) – обобщенное наименование 22 тыс. катыньских жертв, расстрелянных во исполнение катыньского решения;

- katynczyki (катыньчукѝ) и katyniaki (катыняки) – то же, что и катыньские жертвы, около 22 тыс. польских граждан, жертв преступления Katyn, менее официальное название катыньских жертв [53];

- и другие.

Очевидно, имеющиеся во всех этих случаях «катыньские жертвы» (за гибель которых Б.Н. Ельцин ездил каяться в Варшаву перед крестом с надписью «KATYN 1940»), уж точно не жители смоленского поселка Кáтынь или их предки.

В настоящее время Katyn представляет собой польское национальное место памяти (lieux de mémoire в концепции французского исследователя П. Нора) (3) [15, с. 17], а также и наднациональный метоним, акроним (в формулировке А. Эткинда) [25].

Польский премьер-министр Дональд Туск во время выступления на траурной церемонии в Козьих горах 7 апреля 2010 г., стоя на ритуальной площадке, где расходятся дорожки польского военного кладбища Katyn и российской части мемориального комплекса, сказал: «Все мы, поляки, одна большая Katyn».

Название Кáтынский лес для носителей русского языка и las katynski для поляка имеют разную семантическую основу и занимают разное место в национальной культуре памяти.

Для польской национальной идентичности место памяти las katynski как место совершения преступления Katyn сакрально и более чем реально. В сотнях и тысячах статей, буклетов, стихов, молитв, траурных речей и прочих упоминаний о Katyn говорится только о lesie katyńskim. Лишь в редких работах можно встретить единичные употребления названия Козьи горы [41].

Русское название Кáтынский лес политически и исторически нейтрально, так как подразумевает лишь топоним – географическую привязку к определенной местности.

НАЦИСТСКАЯ KATYN

В польской и англоязычной литературе «классическое» описание истории преступления Katyn начинается с 23 августа 1939 г. – даты подписания Договора о ненападении между Германией и Советским Союзом.

Еще две ключевые даты, которые по мнению западных авторов (и, соответственно, их отечественных последователей) являются исходными для понимания событий преступления Katyn, – это 1 сентября и 17 сентября 1939 года. Их символическое наполнение связано с трактовкой событий начала Второй мировой войны как согласованного нападения на Польшу двух тоталитарных государств – Германии и Советского Союза. Данная интерпретация, очевидно, тесным образом связана с усилиями по обвинению Советского Союза в соучастии Гитлеру в развязывании Второй мировой войны и призвана на символическом уровне служить средством уподобления двух политических режимов – гитлеровского и сталинского – и «уравнивания» исторической ответственности двух стран – Германии и СССР – за трагедию народов Европы в период Второй мировой войны.

Очевидно, что польские военные кладбища «Katyn» и «Медное» создавались не просто под воздействием данной концепции, но в полном соответствии с ее основными постулатами: так, на них размещены отлитые в чугуне увеличенные копии Креста сентябрьской кампании – юбилейной медали, учрежденной указом президента польского эмиграционного правительства в Лондоне 1 сентября 1984 г. «в память о боях за защиту и независимость Польско-литовского содружества во время военной кампании с Германией и Советским Союзом в 1939 году». Награждали ею как отличившихся в боях против Германии, так и участвовавших в редких столкновениях с частями Красной армии после 17 сентября 1939 года.

НАЦИСТЫ В СМОЛЕНСКЕ

В феврале 1943 г. победой Советского Союза завершилась беспрецедентная по своим масштабам и значению Сталинградская битва. С победы Красной армии в Сталинградской битве начался отсчет коренного перелома в ходе Великой Отечественной войны и Второй мировой войны.

После поражения под Сталинградом нацистским руководством начала активно использоваться пропагандистская доктрина Kraft durch Furcht («сила через страх»). В целом она была призвана показать всему миру, что Советский Союз хуже, чем нацистская Германия. Осуществить это предполагалось через вызванный страх перед советским строем, который пропаганда должна была представить Европе и всему миру как более кровавый и жестокий, чем нацистский. Содержание пропаганды в рамках кампании «сила через страх» было разным для разных целевых групп.

Для немецкого населения Третьего рейха пропаганда в духе Kraft durch Furcht была призвана поднять моральный дух, сплотить нацию и поддержать надежду на успешное окончание войны. В Германии весной 1943 г. была усилена антисемитская пропаганда, также в это время были проведены акции по «окончательной ликвидации» (уничтожению) еврейских гетто (Краковского, Варшавского и других). Противники описывались с привычной уже риторикой: вермахт воевал с «жидо-большевистским СССР» и его союзниками – «жидами из Англии».

Для оккупированных европейских стран был выдвинут пропагандистский концепт «Новая Европа» – сплочение европейских стран против СССР под эгидой Германии. Страны «Новой Европы» должны были увидеть, что в случае победы Советского Союза в Европе наступит режим более жестокий и кровавый, чем существовал при нацистской оккупации. Германия начала искать те политические силы, которые были готовы сотрудничать с ней против СССР.

Якобы случайное обнаружение весной 1943 г. под Смоленском останков польских офицеров и вброс в мировые СМИ информации о кровавом «жидо-большевистском» преступлении Katyn по времени совпало со сменой политического курса Третьего рейха для оккупированных восточных территорий.

Позиция Гитлера по отношению к Советскому Союзу отражена в одной из его публичных речей этого времени для партийного руководства: «… в этой войне противостоят друг другу буржуазные и революционные государства. Свержение буржуазных государств далось нам легко, потому что они полностью уступали нам в образовании и отношениях. Мировоззренческие государства имеют преимущество перед буржуазными государствами, поскольку они стоят на четкой интеллектуальной основе. Выросшее из этого превосходство принесло нам большую пользу вплоть до Восточной кампании. Но потом мы встретили противника, который тоже представляет мировоззрение, хотя и неправильное» (весна 1943 г.) [27, s. 1927].

Победа Красной армии в Сталинградской битве 1942–1943 гг. показала военную мощь Советского Союза и его возможность противостоять Третьему рейху и его союзникам. Для Гитлера оставалась еще надежда одержать верх над Советским Союзом в пропагандистской – мировоззренческой – войне. На победу в ней фюрер еще надеялся.

О важности пропагандистских кампаний на Востоке и о своих успехах на данном направлении Геббельс записал так: «Вчера: <...> К сожалению, я не продвинулся дальше в вопросе пропаганды на оккупированных восточных территориях и в Советском Союзе» [27, s. 1912]. Запись датирована 17 марта 1943 года.

Геббельсу, очевидно, требовался какой-то новый, значимый в глазах европейского (а может быть, и мирового) общественного мнения информационный повод, который бы выбивался из общего ряда ставших уже рутинными рассказов о «большевистском варварстве». Повод, который не просто соответствовал бы целям и задачам информационной кампании «сила через страх», но и имел бы резонансное звучание в Европе.

И – о чудо! – спустя меньше месяца берлинское радио на весь мир объявит о раскрытии нацистскими властями «чудовищного злодеяния большевиков» и весь мир содрогнется от «ужасов кровавого советского режима». Еще спустя две недели Советский Союз вынужден будет разорвать дипломатические отношения с лондонским эмиграционным правительством.

Что же произошло за это время? Появилась Katyn.

Широко известно и документально доказано, что нацистские власти практиковали сокрытие следов своих преступлений, осуществляемое во исполнение «операции 1005» [15]. В тот период, когда нацисты были уверены в вечном существовании своего Рейха, они особо не скрывались – шили перчатки и абажуры из человеческой кожи, пепел от сожжённых в крематориях тел использовали в качестве сельскохозяйственных удобрений, выкачивали до последней капли кровь у детей для солдат и офицеров вермахта. В лагерях смерти тела людей, умерщвленных в газовых камерах, сжигали в печах крематориев. В концентрационных лагерях и гетто тела расстрелянных закапывали неподалеку. Так, неподалеку от Варшавы (in der Nähe von Warschau) были захоронены в ямах останки расстрелянных узников Варшавского гетто, неподалеку от Кракова (in der Nähe von Krakau) – узников Краковского гетто. При проведении «операции 1005» узников лагерей и гетто отправляли раскапывать захоронения ранее убитых и уничтожать останки. Самих узников-исполнителей впоследствии ждала такая же участь. То же самое практиковалось на оккупированной территории СССР в местах существования концлагерей и лагерей военнопленных.

Обгорелые трупы сожженных женщин и детей

д. Осташково Издешковского района Смоленской области (март 1943 г.).

Жительница деревни держит на руках сожженного ребенка

Фото из фондов Смоленского государственного музея-заповедника

Charred corpses of burnt women and children

of the village of Ostashkovo, Izdeshkovsky district of the Smolensk region (March 1943).

A villager holds a burnt child in her arms

Photo from the collection of the Smolensk region State Museum

Скрыть или уничтожить физические следы своих преступлений на оккупированных советских землях гитлеровцам было невозможно. Германские власти озаботились не захоронениями сотен тысяч советских военнопленных и мирных жителей, евреев, цыган или душевнобольных. Скрыть эти преступления от советского народа было так же невозможно, как и преступления Освенцима и других лагерей смерти и Холокост в целом.

Если бы советское правительство сочло необходимым после освобождения Смоленска обнародовать факт обнаружения массового захоронения в Козьих горах, приписав его нацистам, то это могло если не сорвать, то нанести серьезный удар по геббельсовской кампании «в защиту новой Европы».

Откопанные неподалеку от Смоленска и, что вероятно, свезенные из других мест тела в польском военном обмундировании первоначально, предположительно, планировалось уничтожить для сокрытия следов многочисленных преступлений, совершенных гитлеровцами на территории Смоленской области. Однако Геббельс использовал захоронения в Козьих горах для решения стоявшей перед ним задачи по организации широкомасштабной пропагандистской кампании, направленной против СССР.

Вполне оправданные военно-стратегические прогнозы германских разведслужб о том, что после поражения Гитлера в Сталинградской битве союзники выступят единым фронтом, были оценены Геббельсом как «наша почти абсолютная беззащитность перед британским воздушным террором сегодня» (запись от 9 апреля 1943 г.) [27, s. 1920].

Здесь же, под той же самой датой 9 апреля 1943 г., в дневниках Геббельса зафиксировано: «Вчера: Массовые могилы поляков найдены под Смоленском» (in der Nähe von Smolensk) [27, s. 1920]. Далее главным пропагандистом Третьего рейха была дана интерпретация изложенного факта – то есть, по сути, сформулирована объяснительная модель, которую можно было (или следовало) положить в основу дальнейших заявлений и пропагандистских акций: «Большевики просто застрелили около 10 000 польских пленных, включая гражданских заключенных, епископов, интеллектуалов, художников и т.д., и похоронили их в братских могилах» [27, s. 1920].

В общей своей схеме идея с объявлением виновника преступления пострадавшей стороной и многократным увеличением численности жертв уже неоднократно была опробована гитлеровцами. Можно вспомнить события того же Бромбергского кровавого воскресенья (Bromberger Blutsonntag) 3–4 сентября 1939 года.

Под этой же датой 9 апреля 1943 г. дневники Геббельса зафиксировали указание на начало такой международной информационной кампании: «Вчера: Я сделал так, что к польским массовым могилам приехали нейтральные журналисты из Берлина. Я также пригласил польских интеллектуалов. Там они должны увидеть собственными глазами, что их ждет, если их заветное желание того, что Германия будет побеждена большевиками, действительно бы сбылось (выделено нами. – О.К.)» [27, s. 1920].

Прибывшим 10 апреля в Козьи горы из Варшавы, Кракова и Люблина полякам-«интеллектуалам» нацисты смогли предъявить около 250 тел в двух ямах [40, p. 215].

Геббельсом, как хорошо видно, четко сформулирована цель того, для чего привезли «нейтральных» журналистов и «польских интеллектуалов» под Смоленск на место обнаружения захоронений. Не освещение хода эксгумационных работ, не ознакомление с результатами расследования, не гуманитарная миссия – нет.

Основная цель прибытия в Козьи горы этих специально отобранных нацистскими властями свидетелей – увидеть воочию «кровавое преступление» советского государства, чтобы потом распространить информацию о том, что ждет европейские страны, если Советский Союз одержит победу над Германией в ходе Второй мировой войны. Это полностью соответствовало нацистской пропагандистской доктрине «сила через страх» для Новой Европы. «Сталин хуже, чем Гитлер, а советский строй хуже, чем нацизм», – этот постулат изначально закладывался в идеологическую основу понятия Katyn.

13 апреля 1943 г. соответствующая версия преступления Katyn была озвучена официальными нацистскими средствами массовой информации – через радиосообщения, транслируемые на территории большей части государств-участниц Второй мировой войны, а также оккупированных Третьим рейхом стран. Нацистская Германия обладала мощнейшим пропагандистским аппаратом. По оценкам исследователей, ей было подконтрольно более тысячи газет, радиостанций, типографий, в том числе и тех, которые располагались далеко за пределами ее границ.

Сообщение нацистского радио от 13 апреля 1943 г. гласило: «Из Смоленска сообщают, что местное население указало немецким властям место тайных массовых экзекуций, проведенных большевиками, где ГПУ уничтожило 10 000 польских офицеров. Немецкие власти отправились в Косогоры – советскую здравницу, расположенную в 16 км на запад от Смоленска, где и произошло страшное открытие <…> Офицеры находились сначала в Козельске под Орлом, откуда в феврале и марте 1940 г. были перевезены в вагонах для скота в Смоленск, а оттуда на грузовиках перевезены в Косогоры, где большевики всех их уничтожили» [4, с. 447].

Строгий расчет на изменение расстановки военно-политических сил в условиях коренного перелома хода войны, стремление вбить клин между союзниками, продуманный расчет сплотить антисоветские силы Новой Европы вокруг нацистской Германии – вот основные цели, которые преследовало руководство третьего рейха, объявляя об обнаружении захоронении под Смоленском поляков – «жертв кровавого большевистского преступления».

Обвинение Советского Союза в совершении преступления Katyn, поддержанное мощнейшими информационными акциями, должно было помочь Германии одержать победу над СССР в мировоззренческой войне, которая увеличила бы шансы на победу Германии в войне в окопах.

14 апреля 1943 г. Геббельс записал: «Вчера. Обнаружение 12 000 польских офицеров, убитых ГПУ, сейчас широко используется в антибольшевистской пропаганде. У нас есть нейтральные журналисты и польские интеллектуалы, побывавшие на месте». И далее: «Теперь фюрер также дал нам разрешение опубликовать драматичный отчет в немецкой прессе. Поручаю максимально полно использовать этот пропагандистский материал. Мы сможем прожить на нём несколько недель» [27, s. 1923].

Во исполнение распоряжения Гитлера, который лично контролировал ход Катынького дела, 15 апреля уже будет готов информационный материал этого «драматичного отчета» для прессы. Начиная со следующего дня статьи о катыньском преступлении большевиков начнут публиковаться в главной нацистской партийной газете «Фёлькишер Беобахтер», в издававшейся в столице Польского генерал-губернаторства газете «Краковский гонец» [48], в Японии [12, c. 2] и целом ряде ряде других «нейтральных» изданий.

16 апреля 1943 г. на страницах «Фелькишер Беобахтер» была опубликована первая статья, рассказывающая об обнаруженных «в лесу Katyn» польских захоронениях [32]. Необходимо учитывать, что «Фелькишер Беобахтер» являлась главной партийной газетой национал-социалистической партии Германии (НСДАП), что определяло ее читательскую аудиторию и содержание публикуемых материалов. По сути, это первое публичное представление слова «Katyn» и того содержания, которое оно подразумевало. Сам текст статьи датирован 15 апреля 1943 года.

«Фелькишер Беобахтер» от 16 апреля 1943 года

Nazi Newspaper "Velkischer Beobachter", April 16, 1943

В исторических работах, посвященных проблеме Катыньского дела, нам не удалось обнаружить исследований, посвященных анализу ни данной статьи, ни последующих публикаций о Katyn в официальной нацистской прессе. Очевидно, однако, что упускать из рассмотрения первый, начальный этап концептуализации «Катынского преступления» (или даже всего «Катынского вопроса») нельзя ввиду его огромной значимости для понимания всех его дальнейших «реинкарнаций» в процессе превращения в польское «место памяти» или наднациональный метоним.

Называлась статья «Katyn – пример нападения Иуды на Европу» [32]. Эпиграфом к статье вынесены следующие слова: «Еврей Дэвис: "Мы можем доверять Советскому Союзу!"».

Кто такой этот Дэвис и как он оказался «причастным» к нашей истории?

Оказывается, недовольство и яростные нападки немецкой прессы вызвала опубликованная в британской газете «Evening Standart» статья Д.Э. Дэвиса «Да, мы можем доверять Советскому Союзу», в которой «еврей Дэвис приступает к пропаганде большевизма в Англии» [32].

Д.Э. Дэвис (1876–1958) – американский юрист, дипломат, посол в СССР в 1936–1938 гг., один из организаторов и почетный председатель Национального совета американо-советской дружбы. В своей книге «Миссия в Москву» (1942) он положительно отзывался о Сталине и сталинском режиме. Книга, переведенная на 13 языков, разошлась тиражом в 700 тыс. экземпляров. Весной 1943 г. на основе этих мемуаров был выпущен фильм с таким же названием, рассказывающий о встречах посла со Сталиным, поездках по Советскому Союзу и положительных впечатлениях посла о советском строе. В годы Второй мировой войны Д.Э. Дэвис настойчиво выступал за открытие второго фронта в Европе.

Германии, безусловно, было крайне важно знать, как развиваются отношения между противостоящими ей странами. И не только знать, но и пытаться влиять на эти отношения. В нацистской прессе, например, шла яростная критика и посла СССР в США М.М. Литвинова («этот шулер назначен теперь защищать большевистские интересы в США и ратовать за еврейско-большевистскую войну») [16].

Преамбула первой статьи о Katyn звучит так: «Вместе с 10–12 000 офицеров к большевикам в руки попали более 500 000 польских солдат. Офицеров убили в лесу Katyn, а где солдаты? Первоначально предполагалось объединить их в армию, сражающуюся за большевизм, но об этой армии никогда не было слышно. Польские солдаты исчезли, как и польские дети, эвакуированные в Советский Союз. Судьба, которую еврей Эренбург перед разрушением Европы обещал всем оставшимся в живых из европейских народов, вероятно, постигла их. Они гибнут как бесправные рабы в степях и рудниках Сибири» [32].

Еще одна личность, о которой говорится в самой первой статье о Katyn, – это писатель, поэт и журналист Илья Эренбург, в довоенные годы написавший ряд антифашистских романов. В 1941–1942 гг. И. Г. Эренбург едва ли не каждый день публиковал талантливые острые очерки, вселяющие в советских людей уверенность в неминуемой победе над гитлеровской Германией.

«Красная звезда», 24 июля 1942 г. (№173 [5236])

Soviet Newspaper "Red Star", July 24, 1942 (№173 [5236])

Самый первый текст про Katyn говорит об «озабоченности» нацистских властей судьбой трех групп «пропавших» в сентябре 1939 г. польских граждан – офицеров, солдат и детей.

К весне 1943 г. не было секретом, что интернированные после 17 сентября 1939 г. польские узники войны (POW) были или отпущены после фильтрации, или отправлены вглубь СССР с целью формирования польских военных частей, которые должны были сражаться за свободу своего Отечества против гитлеровской Германии.

Кто же эти «пропавшие» польские граждане, о судьбе которых вспомнили нацистские власти весной 1943 г. в статье о Katyn?

Одна из групп – «польские дети, эвакуированные в Советский Союз», в период после 17 сентября 1939 года. Численность и судьба их нацистам, как следует из текста, неизвестна, однако здесь же утверждается, что «польские дети … гибнут как бесправные рабы в степях и рудниках Сибири». Собственный опыт нацизма по уничтожению детей (польских, еврейских, русских, белорусских, цыганских, украинских и многих других) на оккупированных восточных территориях, по-видимому, повлиял на гитлеровцев в том смысле, что они не видели ничего выходящего за грань разумного в подобном обвинении – оно не казалось им диким и абсурдным. Насильственный угон населения с оккупированных территорий с последующим использованием на тяжелых работах в Дойчланд был характерен как раз для гитлеровской Германии. Обвинение Советского Союза в уничтожении на тяжелых работах польских солдат и польских детей по сути является прямым переносом (проекцией) своих преступлений на субъект, против которого пропаганда и велась.

Интересно и показательно, однако, что в современной трактовке в Польше и на Западе в состав преступления Katyn начинают включать депортацию польского населения в 1940 г., а также детей в июне 1941 года.

Ещё одна группа польских граждан, упоминаемая в статье, – это 10–12 тыс. убитых в «лесу Katyn» офицеров. Заявленная численность польских офицеров в официальных нацистских СМИ объяснялась так: «общее число убитых офицеров оценивается в 10 000, что соответствует примерно полному польскому офицерскому корпусу, взятому большевиками в плен» (Сообщение берлинского радио от 13 апреля 1943 года. Цит. по: [4, с. 447]).

Третья группа – это 500 тыс. польских солдат, из которых на территории Советского Союза предполагалось создать армию, которая будет воевать против нацистской Германии вместе с советскими войсками. В статье задается вопрос: «а где солдаты?», следом дается ответ: «Первоначально предполагалось объединить их в армию, сражающуюся за большевизм, но об этой армии никогда не было слышно. Польские солдаты исчезли…» [32].

Данным утверждением об исчезновении польских солдат нацистская пропаганда сознательно задевает одну из болезненных точек взаимоотношений между Советским Союзом и польским эмиграционным правительством, и снова переворачивает всё с ног на голову. Никаких «пропавших» польских солдат и «пропавших» польских офицеров не было и в помине. Была сформированная в СССР из польских солдат и офицеров армия Андерса, которая отказалась воевать за свободу своего Отечества на Советско-германском фронте и ушла в Иран. Многие ее деятели, в том числе занимавшиеся активной деятельностью по информационной поддержке катыньской провокации, впоследствии осели в Лондоне. Была в Советском Союзе формирующаяся из польских солдат и офицеров 1-я польская пехотная дивизия имени Тадеуша Костюшко (4).

Фелькишер Беобахтер от 16 апреля 1943 г.

Nazi Newspaper "Velkischer Beobachter", April 16, 1943

Нацистский пропагандистский плакат «Katyn», 1943 г.

Nazi propaganda poster "Katyn", 1943

Еще одним интересным источником является карикатура, размещенная рядом с той статьей и озаглавленная «Англия и массовое убийство Katyn» [32]. На иллюстрации изображен «еврейский комиссар-большевик» с отталкивающими чертами лица и лежащие во рве благородной внешности расстрелянные польские офицеры.

Таким образом, первоначальной пропагандистской конструкцией подразумевалась еще одна сторона, непосредственно причастная к преступлению Katyn, – Великобритания. Стоящий слева персонаж на рисунке – глава англиканской церкви Архиепископ Кентерберийский. Довольно улыбаясь, одной рукой он по-дружески похлопывает держащего пистолет «жидо-большевика» по плечу, а другой рукой благословляет. Подпись к рисунку: «Архиепископ кентерберийский: "Жалко, что мы списали Польшу, наша боль была бы велика"» [32].

Возможно предположить, что этим нацисты пытались еще сильнее задеть чувства главной «адресной группы» – поляков. На протяжении переговоров конца 1930-х гг. Великобритания неоднократно обещала Польше военную помощь в случае нападения гитлеровской Германии. Однако, как хорошо известно, этого не случилось. 3 сентября 1939 г. Великобритания объявила Германии войну, однако никакой помощи Польше оказано, в сущности, не было.

Тем не менее, достаточно скоро из содержания пропагандистских материалов Великобритания, благословляющая Советский Союз на кровавую расправу над Польшей, исчезает. Одновременно число жертв Katyn сокращено с 12 тыс. до 10 тыс. человек. В такой скорректированной формулировке описание преступления Katyn стало тиражироваться в последующих газетных публикациях, распространявшихся как на территории Третьего рейха, так и завоеванных европейских стран: 10 тыс. жертв, преступник СССР и невинная Польша.

16 апреля 1943 г. статьи о большевистском преступлении Katyn разошлись по всему миру. Для подтверждения своей правоты у нацистских пропагандистов были выбитые у нескольких местных жителей показания и множество фотоснимков. Из дневника Геббельса от 18 апреля: «Вчера: … Вечером мне показывают снимки Katyn. Они настолько ужасны, что только некоторые из них подходят для публикации» [27, s. 1923].

Известно, что некоторые нацистские преступники порой бывали очень чувствительны к увиденным сценам убийств. Так, по распоряжению Г. Гиммлера, которому стало плохо при виде массового расстрела айнзацгруппой в Минске, группенфюреру СС А. Небе было поручено разработать «более гуманные методы убийства, чем расстрел». В итоге появилось еще одно изощренное средство массового уничтожения людей – так называемые газвагены или душегубки.

Какими бы ужасными не были снимки из Козьих гор, запечатлевшие «кровавое злодеяние большевиков», Геббельсу еще нужно было найти те политические или общественные силы, которые, приняв нацистскую версию Katyn, закрыли бы глаза на творимые нацистами в оккупированных странах массовые преступления.

Говоря о причинах широкой пропагандистской раскрутки катыньской провокации, большинство пишущих на эту тему авторов акцентирует внимание на желании Германии сыграть на противоречиях внутри стран-союзниц и вбить клин между ними. Из поля зрения исследователей, как правило, выпадают мотивы польского эмиграционного правительства, которое с неподдельным энтузиазмом и скоростью ухватилось за предложенную Третьим рейхом тему. При этом можно считать, что хотя катыньская провокация была осуществлена в интересах и общем русле политики нацистов, польское эмиграционное правительство, поддержав ее, также удачно решило часть стоявших перед ней внешнеполитических задач.

16 апреля 1943 г. – в тот же самый день, когда Фелькишер Беобахтер и польские оккупационные газеты разместили информацию о преступлении Katyn – министр обороны польского эмиграционного правительства М. Кукель и министр информации С. Кот по согласованию с премьер-министром В. Сикорским опубликовали заявление, в котором априори согласились с нацистской версией Каtyn и посчитали необходимым провести расследование с участием Международного Комитета Красного Креста (МККК) [10, c. 332].

17 апреля 1943 г. представители Германского Красного Креста и представители Польского Красного Креста практически одновременно обратились в МККК с одной и той же просьбой провести расследование о расстреле польских военнопленных офицеров и других лиц, совершенном большевиками неподалеку от Смоленска. Обе обратившиеся стороны просили МККК отправить в Козьи горы своих представителей [10, c. 332]. О том, что к расследованию катыньского дела подключился Международный Комитет КК сразу же было объявлено по каналам британской общенациональной телерадиовещательной организации BBC [21, c. 159].

Вполне обосновано, что Советский Союз стал рассматривать этот факт как провокацию, организованную совместно германскими властями и польским эмиграционным правительством. И.В. Сталин в послании У. Черчиллю обвинил правительство Сикорского в «сговоре» с Гитлером.

Действительно, к апрелю 1943 г. территория Польши уже три с половиной года находилась под властью гитлеровской Германии. За все это время ни польское эмиграционное правительство, ни Международный Комитет КК, ни Польский Красный Крест не изъявляли желания расследовать какое-либо преступление на территории оккупированной Польши.

При этом деятельность Международного Комитета Красного Креста в годы Второй мировой войны вызывает крайне неоднозначные оценки в мировой историографии, что во многом связано с его позицией по отношению к Холокосту.

МККК был организован 1863 году. Согласно Уставу, в число членов его комитета могут входить от 15 до 25 человек, являющиеся гражданами Швейцарии. Президент и его заместители ответственны, помимо прочего, за внешние связи Комитета. В 1928–1944 гг. президентом МККК являлся социолог-теоретик международного права Макс Губер (1874–1960).

Весьма показательной стороной деятельности МККК, активно включившегося в поддержку и информационное продвижение нацистской версии преступления Katyn, является его политика по отношению к Холокосту.

Еще в 1936 году руководство МККК знало о нацистских планах «окончательного решения еврейского вопроса», однако не предприняло никаких действий как для предотвращения этого преступления, так и попыток информирования мирового сообщества о готовящихся акциях уничтожения [45, p. 183].

Председатель МККК Макс Губер впоследствии объяснил это «молчание» следующим образом: МККК – это нейтральная организация, поэтому та информация, которой она располагает о положении дел в какой-то стране – это конфиденциальная информация и МККК не обязан ее раскрывать третьим странам, даже при наличии запроса [45, p. 187–188].

МККК знал и о концетрационных лагерях, и лагерях смерти. Однако никакой информации об этих преступлениях в международные СМИ также не поступило, никаких международных комиссий в эти места нацистских преступлений не посылалось. Никакой инициативы по расследованию со стороны ни Польского Красного Креста, ни Германского Красного Креста также проявлено не было.

Сознательно выбранная позиция руководства МККК как bystander по отношению к Холокосту в годы Второй мировой войны была объяснена М. Губером следующим образом: существует «одна группа граждан, преследуемых их собственным правительством и которым отказано в правах, которыми пользуются другие его граждане, но, как это ни парадоксально, это не позволяет иностранцам вмешательство в их пользу» [45, p. 190–191]. Итак, согласно логике председателя МККК, иностранное вмешательство для предотвращения Холокоста было невозможно потому, что уничтожаемые евреи были гражданами Германии. Так как Международный Комитет КК позиционировал себя как «нейтральная» организация, то во внутренние дела государств вмешиваться отказывался. Что же изменилось весной 1943 года, когда МКК в лице своих национальных комитетов – германского и польского, действовавших по согласованию с Центральным комитетом, решил нарушить свой нейтралитет и выступить в поддержку Германии?

Польский Красный Крест – одна из немногих довоенных организаций, которой было разрешено продолжать свое существование после начала гитлеровского вторжения в Польскую Республику и организации генерал-губернаторства. «Обнаружение жертв входило в его прямые обязанности», – утверждают авторы монографии «Катынский синдром», говоря о деятельности Польского КК в Козьих горах под Смоленском [21, с. 155].

Главные функционеры Польского Красного Креста заслуживают отдельного внимания. Так, например, Александр Осинский (1870–1956) – генерал-майор Российской Императорской армии (1915), главнокомандующий польской армией на Украине (1918), участник польско-советской войны 1919–1920 гг., генерал-майор Польской армии (1921–1935 гг.), сенатор. С 12 мая 1937 г. по 13 августа 1940 г. являлся президентом Главного управления Польского Красного Креста. После сентября 1939 года бежал из Польши, затем оказался в Лондоне, где стал со-руководителем Польского Красного Креста в качестве председателя Главного совета.

В предвоенные годы А. Осинский являлся руководителем регионального отделения Лагеря национального объединения (OZN) – польской политической проправительственной организацией, отличавшийся антисемитской идеологией. В программе OZN евреи были описаны как «иностранные элементы» для польского народа, которые поэтому «не могут принимать участие в его ˮсегодняшнем днеˮ или вносить свой вклад в его ˮзавтраˮ». Программа OZN, помимо прочего, постулировала «значительное сокращение количества евреев в Польше. Молодежная организация OZN активно участвовала в антисемитских акциях.

В целом, можно констатировать, что представители Польского Красного Креста в годы Второй мировой войны действовали в духе установок М. Губера. Полностью проигнорировав ежедневно совершавшиеся в польском генерал-губернаторстве преступления Холокоста, такие как окончательная ликвидация Краковского гетто 13–14 марта 1943 г., ликвидация Варшавского гетто, которое активно длилось до 16 мая 1943 г., и другие, Польский Красный Крест решил направить своих представителей в далекий Смоленск для проверки нацистского заявления – о советском преступлении Katyn.

До настоящего времени деятельность Международного Комитета Красного Креста, национальных комитетов Красного Креста и их отдельных представителей в контексте становления и развития истории Katyn не становилась предметом научного исследования. Многие материалы о деятельности МККК в годы Второй мировой войны остаются засекреченными, так же, как и информация о судьбах их главных функционеров.

В частности, отчет о собственной деятельности в годы Второй мировой войны, подготовленный Международным Комитетом КК в 1948 г., засекречен и закрыт для научных исследований. Рассекретить его пытались в 1996 г., что вызвало целый ряд публикаций обвинительного характера, после чего проект был снова свернут. Между тем, можно констатировать факт, что деятельность МККК и его национальных – германского и польского – комитетов сыграла далеко не последнюю роль в достижении главной цели катыньской лжи.

26 апреля 1943 г., после ряда провокационных заявлений и демаршей, Советский Союз был вынужден разорвать дипломатические отношения с польским эмиграционным правительством. Одна из целей, к которой стремилась Германия, была достигнута. Польское эмиграционное правительство также получило то, к чему оно давно стремилось – разрыв дипломатических отношений с СССР, повлекший освобождение его от всех принятых ранее обязательств по соглашениям, который формально произошел по инициативе бывшего союзника.

Польское эмиграционное правительство, согласно советско-польскими соглашениям от 30 июля и 14 августа 1941 г., было обязано оказывать Советскому Союзу помощь и поддержку в войне против гитлеровской Германии, однако по факту оно эту помощь и содействие не хотело оказывать и не оказывало. Достаточно вспомнить вывод из СССР армии Андерса, а также поддержку антисоветской деятельности Армии Крайовой.

Польскому эмиграционному правительству было важно, чтобы заслуга в освобождении Польши принадлежала не Советскому Союзу и воюющим плечом к плечу с Красной армией польским солдатам и офицерам Войска Польского. Нужно это было для того, чтобы политическая власть в освобожденной стране не была бы передана просоветскому правительству.

В данном контексте уместно вспомнить, что 1 марта 1943 г. Польская рабочая партия опубликовала декларацию «За что мы боремся?», в которой была сформулирована программа политических и социально-экономических преобразований в Польше после ее освобождения Красной армией: создание временных демократических органов «от гминных до городских советов до правительства включительно», передача государству предприятий, захваченных оккупантами, и установление над ними контроля рабочего класса, возвращение мелким собственникам города и деревни их имущества, раздел между крестьянами помещичьих имений, союз с СССР и ряд других положений [10, c. 341].

Некоторые промежуточные итоги успешно проведенной катыньской провокации были подведены Геббельсом 28 апреля 1943 года. Под этой датой можно найти две принципиально важные для данного исследования записи.

Во-первых, Геббельс, не стесняясь, оставил для истории множество восторженных реплик в свой адрес: «Самая важная тема всей международной дискуссии – это, конечно, разрыв между Москвой и польским эмигрантским правительством. Мнение всех вражеских (радио)вещателей и вражеских газет единодушно в том, что разрыв следует рассматривать как полный успех немецкой пропаганды, особенно моей личности. Восхищаются необычайной хитростью и мастерством, с которыми нам удалось провести сугубо политический вопрос по катынскому делу. В Лондоне крайне обеспокоены успехом немецкой пропаганды. Внезапно в лагере союзников появляются трещины, которые они не хотели видеть раньше. Говорят о полной победе Геббельса. Даже высокопоставленные сенаторы Соединенных Штатов делают очень серьезные комментарии» [27, s. 1924–1925].

Во-вторых, после восторженных словоизлияний Геббельсом делается принципиально важное заявление. Дело в том, что для Гитлера периодически подготавливались информационные материалы, освещающие текущее положение дел на фронте и в стране. Вот, что еще записал Геббельс 28 апреля 1943 года: «Военным в штабе фюрера действительно удалось вытащить фотографии Катыни из кинохроники. К сожалению, у фюрера не было времени посмотреть их лично, и он может захотеть выпустить их для следующей кинохроники. Однако тогда изображения будут настолько устаревшими, что перестанут быть актуальными» [27, s. 1925–1926].

Это значит, что после разрыва дипломатических отношений между СССР и польским эмиграционным правительством из-за катыньской провокации сообщение Гитлеру о КатЫни еще было важно 28 апреля, а вот позднее информация об этом становится уже не только устаревшей, но и неактуальной. Главная цель катыньской провокации была достигнута.

В дневниках Геббельса после приведенной выше записи от 28 апреля 1943 г. упоминание о Катыньском деле (Katyn-Angelegenheit) встречается всего один раз – в записи от 8 мая об обнаруженных в захоронениях немецких патронах: «К сожалению, в могилах Катыни были обнаружены немецкие боеприпасы. Еще предстоит выяснить, как они туда попали. Либо это боеприпасы, которые мы продали советским русским в период мирного соглашения, либо Советы сами бросили в могилы боеприпасы. В любом случае необходимо пока держать это дело в строжайшей тайне; если бы об этом узнали наши враги, все Катынское дело устарело бы» [27, s. 1926].

На этом в деле Katyn, которое Геббельсом было начато и достигнутые итоги которого были им же и подведены, можно было бы поставить точку. Однако теперь необходимо было легализовать и материализовать теоретические построения под названием преступление Katyn. Каждая из заинтересованных в антисоветской катыньской провокации сторон – гитлеровская Германия и польское эмиграционное правительство – подошла к делу по-своему.

Германия своей основной катыньской цели добилась, поэтому ей нужно было только формальное подтверждение «нейтральных» международных судмедэкспертов, что преступление Katyn имело место. Для этого германской стороной была организована поездка в Козьи горы группы международной комиссии экспертов.

Напомним, что в начале апреля на место обнаружения захоронений германская сторона привозила «нейтральных» журналистов из разных стран, задача которых состояла в информационной поддержке распространения информации и фотоснимков о преступлении Katyn. Заключение международных судмедэкспертов должно было придать статус объективности заявленной версии, перевести его из сферы пропаганды в область реально произошедших (признанных таковыми) событий.

По факту, международная «независимая» комиссия судмедэкспертов прибыла в Козьи горы делать свои выводы только 28 апреля 1943 г. – уже после того, как катыньская провокация сделала свое дело (разрыв дипотношений между Советским Союзом и польским эмиграционным правительством произошел двумя днями ранее).

Представители 12 стран пробыли в Козьих горах всего три дня (с 28 по 30 апреля). За это время они успели осмотреть подготовленные германской стороной к их приезду 982 трупа, из которых было идентифицировано около 70% [51, s. 59]. «Независимым» судмедэкспертам оккупационные власти разрешили провести вскрытие только девяти трупов. Также их отвезли посмотреть подготовленную сотрудниками службы безопасности СД выставку, на которой в деревянных ящиках-витринах под стеклом экспонировались находки катыньского леса.

Члены международной комиссии осматривают экспонаты 1-й катыньской выставки,

подготовленной офицерами немецкой службы безопасности СД

Members of the International commission visiting the 1st Katyn exhibition,

prepared by the officers of the Nazi German security service SD

В отношении к результатам деятельности этой комиссии и отдельных ее представителей существуют серьезные разногласия. Основные из них связаны с оценкой степени объективности (той самой независимости), которую было позволено проявлять членам комиссии, а также степенью влияния экспертных заключений международных специалистов на уже существовавшую к моменту их приезда в Козьи горы нацистскую версию преступления Katyn [6]. Впоследствии заключение международной комиссии экспертов было включено в качестве одного из документов в официальные «Амтлихен материалз» [22].

Деятельность польской стороны по легализации и материализации преступления Katyn была организована по совсем другим принципам. Как широко известно, в Козьих горах под Смоленском с 29 апреля по 3 июня 1943 г. работала так называемая Техническая комиссия Польского Красного Креста (ТК ПКК). В исследованиях, посвященных катыньской тематике, внимание уделяется только деятельности ТК ПКК по эксгумации останков и их идентификации, а вот история ее организации и взаимодействие с немецкими властями слабо или почти не освещена. Как правило, авторы ограничиваются формальной констатацией, что «комиссия была создана после обращения властей генерал-губернаторства в Польский Красный Крест» [21, с. 155].

На территории Генерал-губернаторства (до июля 1940 г. – Генерал-губернаторство для оккупированных польских областей) (5) действовало законодательство Германии, но большинство его жителей, разделенных на несколько категорий, не имели статуса граждан Германии и были ограничены в правах. Вся администрация была немецкой. Что мы знаем о «властях генерал-губернаторства», которые якобы выступили с инициативой о необходимости работы ПКК по эксгумации и идентификации польских останков в далеких Козьих горах?

Ганс Франк

Hans Frank

Йозеф Бюлер

Joseph Buehler

Весь период оккупации Польши ее возглавлял генерал-губернатор Ганс Франк (1900–1946) – рейхсляйтер НСДАП (1934–1942), один из главных организаторов масштабного террора и уничтожения польского и еврейского населения Польши. На Международном Нюрнбергском трибунале был одним из 24 главных нацистских преступников, приговорен к смертной казни.

Йозеф Бюлер (1904–1948) – статс-секретарь Генерал-губернаторства (май 1940–1945), бессменный заместитель Ганса Франка. Член НСДАП, бригаденфюрер СС. В качестве представителя генерал-губернаторства Бюлер принимал участие в конференции в Ванзее (20 января 1942 г.), на которой обсуждался вопрос об окончательном решении «еврейского вопроса в сфере германского влияния в Европе». Бюлер заявил о важности «как можно скорейшего решения еврейского вопроса в генерал-губернаторстве» и призвал Гейдриха начать «окончательное решение» в генерал-губернаторстве, где не существовало «транспортных проблем». Бюлер выступал в качестве свидетеля со стороны защиты Г. Франка на Нюрнбергском трибунале, затем был экстрадирован в Польшу, где за преступления, совершенные против человечества, казнен в Кракове в 1948 году.

По инициативе и с ведома именно этого ответственного за массовый террор и Холокост руководства генерал-губернаторства было направлено обращение в Польский Красный Крест с просьбой отправить представительство под Смоленск, чтобы эксгумировать и идентифицировать обнаруженные там польские останки.

Сам Польский Красный Крест, как отмечалось выше, действовал по согласованию с руководством МККК и в русле его общей политики, полностью игнорируя преступления против еврейского населения, массово совершаемых германскими властями на территории генерал-губернаторства (Холокост).

По поводу этого нацистского обращения о создании комиссии Польский Красный Крест провел консультации с руководством Армии Крайовой, которое, по сути, руководило подпольным польским государством. В итоге было решено организовать Техническую комиссию ПКК из пяти человек во главе с членом главного правления ПКК К. Скаржиньским.

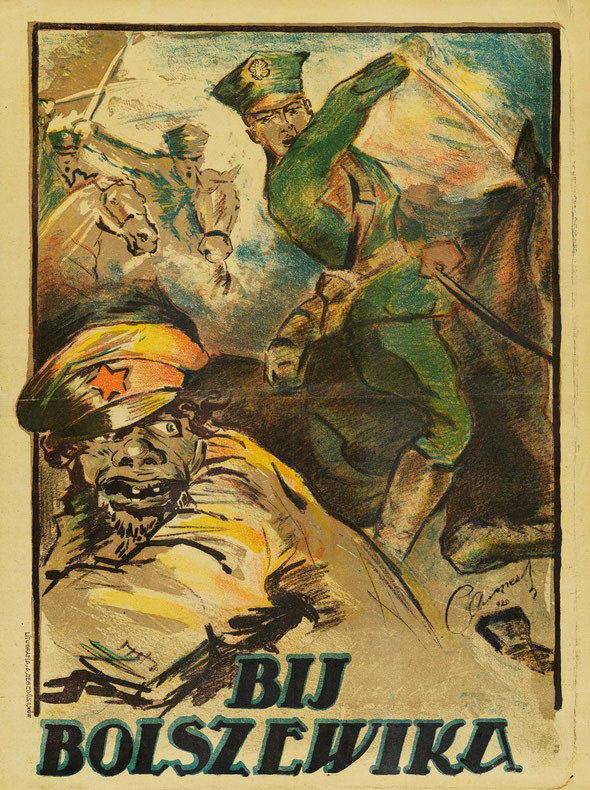

Казимеж Скаржиньский (1887–1962) принадлежал к старинному шляхетскому роду, образование получил в иезуитской гимназии в Вене, окончил Университет политических наук в Париже, затем Высший коммерческий институт в Антверпене. В 1920 г. записался добровольцем в польскую армию и как кавалерист 203-го уланского полка сражался против Советской России. В 1924–1939 гг. был вице-президентом, а затем президентом французско-польской целлюлозной компании. В своем «Рапорте из Катыни» подробно описал эксгумацию, к которому прилагался составленный в июне 1943 г. список убитых. После освобождения Польши Красной армией сначала скрывался, а затем бежал (декабрь 1945 г.), передав перед этим в посольство Великобритании дополненный вариант «Рапорта из Катыни» [44].

К. Скаржиньский (1887–1962) –

руководитель технической комиссии Польского Красного Креста в Козьих горах в 1943 году

Портрет работы С. Норблина, 1935 г.

Skarzynski (1887-1962) -

Head of the Technical commission of the Polish Red Cross in the Goat Hills in 1943.

Portrait by S. Norblin, 1935

Армия Крайова (до 14 февраля 1942 г. называвшаяся Польские вооруженные силы) – главная структура военно-политического подполья, подчиненная польскому эмиграционному правительству. Она была создана кадровыми офицерами довоенной армии для борьбы против, как они считали, тогдашних главных врагов независимой Польши – Германии и СССР. Исходя их концепции двух врагов, руководители АК рассчитывали на восстановление польского государства при поддержке Великобритании и США после того, как Германия и СССР будут обескровлены взаимным противостоянием [14].

Генерал и публицист С. Ровецкий (1895–1944), на стол к которому попадали отчеты о деятельности Технической комиссии ПКК, в годы Первой мировой войны воевал в составе 1-й бригады польских легионов против Российской империи, затем участвовал в польско-советской войне 1919–1920 гг. С 14 февраля 1942 года по 30 июня 1943 года С. Ровецкий был главным комендантом (командующим) Армии Крайовой, являлся сторонником концепции двух врагов. После ареста Ровецкого АК возглавил его заместитель Т. Коморовский. Уже при нем происходила доставка ящиков с катыньскими вещдоками в Краков, их обработка и последующая эвакуация от приближающихся войск Красной армии.

Т. Коморовский (1895–1966) в годы Первой мировой войны сражался на стороне Австро-Венгрии против Российской империи, с 1918 г. – в польской армии, командовал эскадроном и уланским полком в ходе польско-советской войны 1919–1920 гг. После создания Армии Крайовой был заместителем С. Ровецкого, после ареста которого назначен ее командующим. 1 августа 1944 г., при подходе Красной армии к Варшаве, именно Т. Коморовский отдал приказ о начале восстания, окончившегося катастрофой для польского народа.

Техническая комиссия Польского Красного Креста прибыла в Козьи горы 29 апреля 1943 г., также уже после того, как Германия достигла своей цели использования катыньской провокации.

Время работы Технической комиссии ПКК в Козьих горах было намного более продолжительным, чем комиссии международных экспертов – не три дня, а более месяца (с 29 апреля по 3 июня 1943 г.). Комиссия ПКК прибыла отдельно от «нейтральных» международных экспертов и работала принципиально отдельно от них. Также члены ТК ПКК показательно дистанцировались и от немцев – не садились с ними за один стол, при фотографировании стояли обособленной группой [21, с. 155]. Функции, выполняемые ТК ПКК, принципиально отличались от деятельности «нейтральной» международной комиссии.

Заметим, что первые идентификационные списки стали публиковаться в польских оккупационных газетах с 16 апреля 1943 г., то есть сотни личных установочных данных (имя, фамилия, воинское звание) «расстрелянных НКВД» польских офицеров к этому времени нацистам уже были известны. И известны заранее. Ряд исследователей сходится в том, что в руки к германским оккупационным властям попала часть архива УНКВД по Смоленской области (в том числе и польские списки), захваченная в июле 1941 г., также как и часть областного партийного архива [9]. Первые германские идентификационные списки по форме очень кратки – в них указаны только воинские звания, имена, фамилии и, крайне редко, какая-то дополнительная информация. По форме они соответствуют этапным спискам, за исключением указания года рождения. Это понятно: год рождения при эксгумации установить крайне проблематично.

Техническая комиссия ПКК действительно могла помочь германской стороне идентифицировать останки. Международный Красный Крест и его национальные подразделения, в которые запросы о судьбе пропавших польских военнослужащих и гражданских лиц поступали на всем протяжении Второй мировой войны, обладал обширнейшей базой данных о тех польских гражданах, прежде всего военных, которые пропали после 1 сентября 1939 г.: их установочными биографическими данными, домашними адресами, сведениями о родственниках, письмами, в том числе с дневниковыми описаниями, фотографиями и прочими материалами личного происхождения. Еще 3 декабря 1941 г. во время встречи в Кремле со Сталиным премьер-министр польского эмиграционного правительства – и по совместительству глава Польского КК – Сикорский озвучил цифру в 3845 польских офицеров, «пропавших» с сентября 1939 года.

Согласно опубликованным итоговым отчетам нацистской / польской комиссии всего из восьми могил было эксгумировано 4143 трупа, 2815 / 2730 из которых было идентифицировано.

Если учесть, что к моменту пребывания в Козьих горах международной комиссии экспертов (28–30 апреля) было готово для осмотра 982 трупа, из которых 70% было идентифицировано, то за один месяц комиссии ПКК удалось выполнить свои задачи по эксгумации около 3 тыс., идентификации около 2 тыс. и перезахоронению более 4 тыс. останков.

В описаниях деятельности ТК ПКК можно найти упоминания о том, что при проведении работ ей помогало около 160 советских военнопленных и местных жителей [21, с. 155].

Советские военнопленные использовались в качестве рабочей силы с самого начала проведения работ. Так, в воспоминаниях бургомистра оккупированного Смоленска Б. Меньшагина говорится о том, что во время его поездки в Козьи горы 18 апреля 1943 г. он видел, как «в траншеях еще копались русские военнопленные, а на площадке стояло несколько немецких солдат с винтовками» [1, с. 503].

В «Рапорте из Катыни» Скаржиньского упоминается о том, что «весь комплекс работ был осуществлен членами Технической комиссии ПКК, немецкими властями и жителями окрестных сел, число которых составляло в среднем 20–30 человек в день. Присылались также большевистские пленные в количестве 50 человек в день – они использовались исключительно для раскапывания и засыпки могил и уборки территории» (6) [17].

Руководитель польского КК в своем отчете называет имена и фамилии только своих польских коллег и тех германских деятелей, с которыми он тесно общался. «Местных жителей» из окрестных смоленских деревень, а также истощенных голодом «большевистских пленных», пригоняемых на работы в Козьи горы из расположенного в 15 км города Смоленска, выходец из старинного шляхетского рода Скаржиньский считал «по головам» и в июне 1943 г. смог назвать только приблизительное их число: 20, 30, 50 человек в день… И так каждый день! А ведь это были именно те советские граждане, на чью долю выпал труд по эксгумации и перезахоронению останков поляков, обнаруженных в Козьих горах.

Польские авторы и их отечественные последователи не поднимают вопроса о том, как сложилась судьба тех советских граждан, которые весной–летом 1943 г. выполнили основной объем работ по эксгумации польских останков в Козьих горах, последующему их захоронению и обустройству польского кладбища. От них не осталось ни имен, ни фамилий. В официальной польской версии «катыньского преступления» не нашлось ни одного слова благодарности в адрес этих советских граждан или сожаления об их участи. В современных польских катыньских молитвах также не упоминаются и не поминаются эти катыньские жертвы, несмотря на то, что их судьбы и их жизненный путь навсегда связаны с польско-нацистской катыньской провокацией.

Военнопленные из лагеря, расположенного в Смоленске, и жители близлежащих к Козьим горам деревень направлялись на работы по решению германских оккупационных властей, по окончании работ все они были расстреляны и захоронены неподалеку.

В сентябре 1943 г. – при освобождении Смоленска и узников дулага-126 Красной армией – в живых не было ни одного участника работ в Козьих горах и ни одного человека, хотя бы слышавшего рассказ об этом. Ни советской комиссии Бурденко, ни американской комиссии Мэддена не удалось ни отыскать, ни допросить ни одного из этих советских военнопленных.

В то же время всё в том же «Рапорте» Скаржиньского описана идиллическая сцена прощания: «Покидая кладбище, комиссия поблагодарила за сотрудничество поручика Словенцика, подпоручика Босса, немецких унтер-офицеров и солдат и русских рабочих за крайне тяжелый двухмесячный труд по эксгумации останков» [17].

Заслуживший слова благодарности польских представителей Красного Креста обер-лейтенант Словенцик (Словенчик), как упоминается здесь же в комментариях, являлся «командиром роты пропаганды (Aktivpropagandakompanie)». «Подпоручик Босса» – имеется в виду лейтенант полевой полиции Фосс, который весной 1943 г. являлся ответственным за исполнение на месте основных мероприятий катыньской провокации [20; 22, s. 18 и др.].

Первая мемориализация преступления Katyn периода Второй мировой войны (так называемая Nazi-Katyn) была осуществлена в мае–июне 1943 г. в виде оформления захоронений на оккупированной гитлеровцами советской земле в Козьих горах под Смоленском.

Согласно «Рапорту из Катыни» Скаржиньского, кладбище представляло собой шесть братских могил квадратной формы, расположенных по обе стороны от центральной дорожки. Могилы по периметру были обложены дерном, дерном же в центре каждой могилы был выложен равноконечный крест. В двух индивидуальных могилах были захоронены польские генералы Б. Богатыревич и М. Сморавиньский. На каждой могиле был установлен 2,5 метровый католический крест. В день отъезда из Катыни последних членов Технической комиссии ПКК, то есть 9 июня 1943 г., на самом высоком кресте на 4-й могиле был повешен венок, сделанный из жести и проволоки одним из членов комиссии. Венок был выкрашен в черный цвет, в середине располагался терновый венец из колючей проволоки, в центре венца к деревянному кресту был насквозь прибит польский орел с офицерской фуражки [17].

По прошествии 33-х лет эта христианская символика – терновый венец и пригвожденный к кресту мученик, символизировал которого польский гербовый орел, – будет один в один повторена на памятнике под названием «Memorial Katyn», установленном в Лондоне в 1976 году [39].

Подписание соглашения о сооружении памятника Memorial Katyn в Лондоне

Signing of an agreement on the construction of the monument Memorial Katyn in London

O prawde i sprawiedliwosc. Pomnik katynski w Londynie. SPK-Gryf Publications, London, 1977. S. 32

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Польша, символически изображенная в виде польского гербового орла Речи Посполитой в терновом венце из колючей советской проволоки, на долгие 50 лет станет одним из основных символов противостояния в Европе периода холодной войны.

В годы холодной войны нацистская версия преступления Katyn получит свое «второе дыхание». Польское эмиграционное правительство займется дальнейшими теоретическими разработками, в результате которых число катыньских жертв будет увеличено до 14,5 тыс. человек.

Признание руководством Советского Союза в 1990 году вины в совершении преступления Katyn, вновь поддержанное мощнейшими информационными акциями, помогло Германии и США одержать победу над СССР в мировоззренческой войне, которая привела к разрушению Советского государства в 1991 году.

Примечания

- Сразу же после столкновения 3-4 сентября 1939 г., немецкий отдел пропаганды сделал огромное количество фотографий, запечатлевших немецких жертв нападения поляков. 7 сентября 1939 г. Германское информационное агентство начало распространять первые репортажи о «Бромберге – городе ужасов». Немецкими властями были приглашены иностранные «нейтральные» журналисты, чтобы лично увидеть ужасы, творимые поляками. Нацистский военный журналист зондерфюрер Э.Э. Двингер (E.E. Dwinger) по личной просьбе Геббельса написал об этом событии книгу Der Tod in Polen. Die volksdeutsche Passion, изданную в 1940 году. Число немецких жертв в 103 человека, в книге было определено как 5 тыс. человек, а сами события были описаны как заранее спланированная поляками акция по уничтожению этнических немцев.

- Государственный архив Смоленской области (ГАСО). Ф. Р-1630. Оп. 2. Д.28. Л. 113–113об. Из акта представителей воинской части №14164 и жителей с. Катынь-Успенское об ограблении, издевательствах и уничтожении немецко-фашистскими оккупантами мирных жителей с. Катынь Смоленского района / Без срока давности: преступления нацистов и их пособников против мирного населения на оккупированной территории РСФСР в годы Великой Отечественной войны. Смоленcкая область : Сборник архивных документов / отв. ред. серии Е.П. Малышева, Е.М. Цунаева; отв. ред. О.В. Иванов; сост. С.В. Карпова. — М. : Фонд «Связь Эпох»: Кучково поле, Музеон, 2020. – 656 с.: ил. С.332–333.

- В данном случае мы используем термин «место памяти», который ввел французский исследователь Пьер Нора.

- Постановление Государственного комитета обороны СССР № 3294 от 6 мая 1943 года «О формировании 1-й польской пехотной дивизии имени Тадеуша Костюшко». Формирование дивизии началось 14 мая 1943 г. в Селецких военных лагерях под Рязанью.

- Генерал-губернаторство для оккупированных польских областей (Generalgouvernement für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete) было образовано 26 октября 1939 г. в соответствии с приказом рейхсканцлера А. Гитлера от 12 октября 1939 года. С 31 июля 1940 г. оно стало называться Генерал-губернаторство (Generalgouvernement).

- «Большевистские военнопленные» – определение, которое широко использовалось в Польше в антисоветской пропагандистской риторике периода польско-советской войны 1919–1920 гг. и в последующие годы. Согласно данным проф. Г.Ф. Матвеева, не менее 25–28 тыс. советских военнопленных умерли в польском плену от голода, холода, антигуманных нечеловеческих условий содержания, издевательств и произвола польской администрации (в том числе и произвольных расстрелов и убийств).

Список литературы

- Борис Меньшагин: Воспоминания, Письма, Документы / Сост. и подг. текста П.М. Полян. М.; СПб.: Нестор-История, 2019. – 824 с.

- Воробьев М., Титов В., Храпченков А. Смоляне – герои Советского Союза. М.: Московский рабочий, 1966. – 648 с.

- Иванов Ю. Г. Как правильно произносить: Катынь или Катынь? – Иванов Ю. Г. Город-герой Смоленск. 500 вопросов и ответов о любимом городе. Смоленск: Русич, 2015. – 384 с.

- Катынь. Март 1940 г. – сентябрь 2000 г. Расстрел. Судьбы живых. Эхо Катыни. Документы. М.: Весь Мир, 2001. – 688 с.

- Катынь. Пленники необъявленной войны. Документы и материалы / под ред. Р.Г. Пихои, А. Хейштора; сост.: Н.С. Лебедева, Н.А. Петросова, Б. Вощинский, В. Матерский. М.: Международный фонд «Демократия», 1999. – 608 с.

- Катынские доказательства проф. Франтишек Гаек. 9 июля 1945 г. – Немцы в Катыни. М.: ИТРК. С. 132–165.

- Кикнадзе В. Г. «Катынь» в пропаганде, правовых оценках и судебных решениях, научном, политическом и общественном дискурсе. – Вопросы истории. 2021. № 4(1). С. 74–93. DOI: 10.31166/VoprosyIstorii202104Statyi04

- Кикнадзе В. Г. Российская политика защиты исторической правды и противодействия пропаганде фашизма, экстремизма и сепаратизма: Монография. М.: Прометей, 2021. – 800 с.

- Кодин Е. В. «Смоленский архив» и американская советология. Смоленск. гос. пед. ун-т – Смоленск: СГПУ, 1998 – 286 с.

- Краткая история Польши: С древнейших времен до наших дней. М.: Наука, 1993. – 528 с.

- Лебедева Н. С. Катынь: Преступление против человечества. М.: Прогресс–Культура, 1994. – 352 с.

- Новый путь, 18 апреля 1943 г.

- Нора П. Проблематика мест памяти. Франция-память. – П. Нора, М. Озуф, Ж. де Пюимеж, М. Винок / Пер. с фр.: Дина Хапаева. СПб.: Изд-во С.-Петерб. ун-та, 1999. С. 17-50.

- Носкова А. Ф. Документальная публикация «Как польское вооруженное подполье "помогало" Красной Армии разгромить нацистскую Германию. 1944–1945 гг.». – URL: https://archives.gov.ru/index.php?q=library/poland-1944-1945/foreword.shtml

- Операция 1005. – URL: https://www.yadvashem.org/ru/holocaust/lexicon/aktion-1005.html

- От арестанта до посла в США. – Новый путь. № 19. 18 декабря 1941 г.

- Скаржинский К. Рапорт из Катыни. Отчет Польского Красного Креста. Варшава, июнь 1943 г. [Report from Katyn. Report of the Polish Red Cross. Warsaw, June 1943]. – «Одродзене», № 7, 1989. – URL: http://www.katyn-books.ru/library/katyn-svidetelstva-vospominaniya12.html

- «Убиты в Калинине, захоронены в Медном». Книга памяти польских военнопленных – узников Осташковского лагеря НКВД, расстрелянных по решению Политбюро ЦК ВКП(б) от 5 марта 1940 года. Отв. сост. А.Э. Гурьянов. Тт.1–3. Москва, Общество «Мемориал», 2019.

- Убиты в Катыни. Книга памяти польских военнопленных – узников Козельского лагеря НКВД, расстрелянных по решению Политбюро ЦК ВКП(б) от 5 марта 1940 года. Отв. cост. А.Э. Гурьянов. Международное общество «Мемориал» (Москва), Центр КАРТА (Варшава). М., Общество «Мемориал» – Издательство «Звенья», 2015. – 932 с.

- Фосс. Обращение к населению. – Новый путь / Der Neu Weg, 3 мая 1943 г.

- Яжборовская И. С., Яблоков А. Ю., Парсаданова В. С. Катынский синдром в советско-польских и российско-польских отношениях. М.: Российская политическая энциклопедия (РОССПЭН), 2001. – 496 с.

- Amtliches Material zum Massenmord von KATYN. Berlin. Zentralverlag der NSDAP. Franz Eher Nachf. GmbH. Gedruckt im Deutschen Verlag, 1943 (in German).

- Die 12 000 polnischen Offiziere von judischen Kommandos gemeuchelt. – Volkischer Beobachter. Berlin, Freitag, 16, April 1943. S. 1–2 (in German).

- England und der Massenmord von Katyn. – Volkischer Beobachter. Berlin, Freitag, 16, April 1943. S. 1 (in German);

- Etkind A. Remembering Katyn. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012. – 214 р. (in English)

- Falsehood in War-Time by Arthur Ponsonby MP 1929. Scanned, serialized and posted by Geoffrey Miller, on the WWI Listserve / (in English). – URL: http://www.vlib.us/wwi/resources/archives/texts/t050824i/ponsonby.pdf

- Joseph Goebbels. Tagebücher 1924–1945. Band 4. 1940–1942. Herausgegeben von Ralf Georg Reuth. Piper München Zürich, 1999. (in German).

- Kaczorowski R. Slowo wstepne. – Katyn. Ksiega Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego. Rada Ochrony Pamieci Walk I Meczenstwa. Warsawa, 2000. S. VII–IX. (in Polish)

- Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment / ed. by A. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva & W. Matersi, Yale University Press, 2007. (in English)

- «Katyn. Documents of Genocide». Documents and Materials from Soviet archives turned over to Poland on October 14, W. Materski ed., 1992. (in Polish)

- Katyn. Dokumenty ludobojstwa. Dokumenty i materialy archiwalne przekazane Polsce 14 pazdziernika 1992 r. Warszawa: Instytut Studiów Politycznych Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1992.

- Katyn – ein Beispel fur Judas Anschlag auf Europa. – Volkischer Beobachter. Berlin, Freitag, 16, April 1943. S. 1 (in German).

- Katyn. Ksiega Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego. Rada Ochrony Pamieci Walk I Meczenstwa. Warsawa, 2000. – LXXVI + 776 s. (in Polish)

- Ledford K. F. Mass Murderers Discover Mass Murder: The Germans and Katyn, 1943. – Case Western Ressarve. Journal of International Law. Vol. 445. Iss. 3 (2012). Pp. 557–589. (in English). – URL: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol44/iss3/22

- Mackiewicz J.The Katyn Woods Murders. Holis & Carter, 1951. (in English)

- [Mackiewicz J.] Zbrodnia Katynska w swietle dokumentow / z przedm. Władysława Andersa. London: Gryf, 1948 (in Polish)

- Miednoje: Ksiega Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego. Rada Ochrony Pamieci Walk I Meczenstwa. Warsawa, 2006. 2 v. : ill.

- Moszynski A. Lista Katyńska. Jeńcy obozow Kozielsk, Ostaszkow, Starobielsk, zaginieni w Rosji sowieckiej. Warszawa: Agencja Omnipress – Społdzielnia Pracy Dziennikarzy, Polskie Towarzystwo Historyczne, 1989. – 336 c. (in Polish)

- O prawde i sprawiedliwosc. Pomnik katynski w Londynie. SPK-Gryf Publications, London, 1977. – 96 s. (in Polish)

- Paul A. (M. Allen) Katyn`: Stalin`s massacre and the triumph of truth. Northern Illinois University Press. DeKalb, 2010. – 430 р. (in English)

- Peszkowski Z. A.J., Zdrojewski S.Z.M. Kalendarz na Rok 2000. Minski. Lodz – Warszawa – Orchard Lake, styczen 2000 r. Maj, 26–28. (in Polish)

- Przewoznik A. Cmentarz w Katyniu. – Katyn. Ksiega Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego. Rada Ochrony Pamieci Walk I Meczenstwa. Warsawa, 2000. S. LIII–LX. (in Polish)

- Przewoźnik А., Adamska J. Katyn. Zbrodnia, prawda, pamiec . Swiat Ksiazki, 2010. – 554 s. (in Polish)